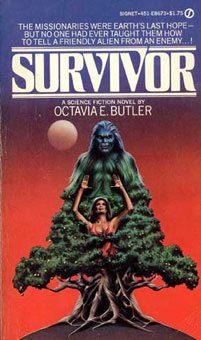

Survivor (1978) is part of the Pattern series, but has not been reprinted since 1981. Butler repudiated the novel and refused to allow it to be reprinted:

When I was young, a lot of people wrote about going to another world and finding either little green men or little brown men, and they were always less in some way. They were a little sly, or a little like “the natives” in a very bad, old movie. And I thought, “No way. Apart from all these human beings populating the galaxy, this is really offensive garbage.” People ask me why I don’t like Survivor, my third novel. And it’s because it feels a little bit like that. Some humans go up to another world, and immediately begin mating with the aliens and having children with them. I think of it as my Star Trek novel.

All I can say is, she clearly watched a better grade of Star Trek than I ever did. I can understand her problem with the biology, but what she seems to be saying there is that Survivor is a dishonest novel. Well, I kind of like it. I’m sorry you can’t read it.

I was wrong in the comments to the last post when I said it was only tenuously connected to the other Pattern books. It is, as I remembered, almost entirely set on another planet. But it’s essential that the humans in the book—and especially Alanna, the protagonist and titular survivor—came from that disintegrating Earth. They have lived through a lot of betrayal (“a clayark friend” is an untrustworthy friend, from the people who deliberately spread the plague) and crisis. Alanna herself was a “wild human” before being adopted by the colonising missionaries. Between the ages of eight and fifteen, after her parents died as society collapsed, she lived alone and wild. Every society she becomes part of afterwards she blends into and adopts protective coloration. The missionaries who take her in are themselves not your usual humans in space. They’ve taken a one way journey and are particularly obsessed with keeping themselves human, because they have seen the clayarks. And their spaceship is powered by a telekinetic who dies on arrival. Nobody’s boldly going—more like fleeing. They’re space refugees much more than space pioneers.

The basic story of Survivor is in fact fairly standard for written SF. Some humans go to colonize another planet, it has intelligent aliens on it, they have trouble with them, the protagonist is captured by the aliens and figures out how to get along with them. I can think of a pile of books this describes: Judith Moffett’s Pennterra, Cherryh’s Forty Thousand in Gehenna, Marion Zimmer Bradley’s Star of Danger—hang on a moment, why are all those written by women? Is there something I’m not seeing? And why have I read all these books so I have their names on the tip of my finger? Why is this a theme and a story I’m always happy to rediscover? Is there actually a subversive feminist thing going on here? (You think?) Certainly Alanna is a powerful central female character of a kind that was still quite unusual in 1978, and even in the early eighties when I read Survivor. And certainly this thing of getting along with aliens, especially in the light of the Tiptree story, is interesting. I think Survivor can definitely be positioned with a lot of feminist SF.

It is in fact an interesting variation on the theme outlined above. Firstly, Alanna, the human protagonist, is very atypical. She’s from Earth, but not an Earth or a culture that feels familiar. (Forget Star Trek‘s Middle America in Space.) Even beyond what’s happened to Earth, she’s very young and she has that feral background. It would be a much more ordinary book with a protagonist designed to be easy to identify with. It’s the characterisation of Alanna that makes this rise above the norm. Also, the alien culture is nifty. They’re all Kohn, but the humans interact with two nations of them, the Garkohn and the Tehkohn. They have fur that changes colour and flashes as part of their communication. The Garkohn, with whom the humans initially make friends, marks membership by deliberately eating an addictive fruit that grows only in their region. I’d also argue with Butler’s characterisation of the aliens (in the interview) as “somehow lesser.” They’re not as technologically advanced as the humans, certainly, but in every other way they have them beaten and surrounded. There’s very little doubt that the human colony on the planet is going to be utterly assimilated. The aliens are far better fitted to survive. And as we know, humans on Earth aren’t doing well, and many of the other colonies being sent out are taking telepathic children along as cuckoos. As a universe, it looks as if aliens are winning hands down.

The survival theme is obvious, the novel’s other theme is belonging.

When people talk about “write what you know” instead of writing SF, I always say that the one thing we’re all qualified to write is the story of being thirteen years old and surrounded by aliens. There’s a way in which Survivor is that—again especially in the light of “The Women Men Don’t See.” Alanna’s eighteen when she goes to the alien planet, twenty at the end of the book. To begin with she doesn’t fit in anywhere. The humans are just as alien to her as the aliens are, more alien in some ways, she more naturally fits with the aliens. This is the story of how she finds her place and defines herself as belonging. Her place is found among the aliens, and by the (biologically improbable) child she bears to the blue-furred alien leader who first raped her but who she later comes to love. I find that trope a lot more problematic than the human/alien interfertility.

The other thing that’s weird in this book is color. Not among the humans. The humans are a mixture of black and white, and Alanna describes herself as “half-black and half-Asian.” (I notice there was no question of disguising this on the cover. Both US and UK covers went with the aliens.) The remaining racial prejudice that causes one colonist to suggest that Alanna would be better adopted by black parents than white ones is raised only to make the point that everyone is human. But then we get to the aliens. The furry (but humanoid, and inter-fertile) Kohn are literally “people of color”—they are heavily furred and their fur changes colour as part of communication. Their natural fur shade determines their caste, the bluer the better and the yellower the worse. I’m sure Butler can’t have done this unconsciously, with color of all things, but I find it hard to understand what she intended with the text’s neutral-to-positive depiction of color as caste and destiny for the aliens. The Garkohn, who have killed off their blue-furred upper classes, are the addicted bad guys, and the Tehkohn, who retain the caste system complete, are the ones Alanna chooses to belong to. Her leader husband has luminously blue fur. If this is possibly what later made Butler uncomfortable and want to suppress the book, I can see it. I mean I can also see all sorts of thought-provoking ways in which the alien color-change fur could be an interesting thing to do with race… but that really doesn’t seem to be what she is doing. The goodness of blue-ness goes apparently unquestioned. Weird, as I said.

The writing is just where you’d expect it to be, better than Mind of My Mind, not quite as good as Wild Seed. The characterisation, of humans and aliens is excellent all the way through. The story is told in past and present threads, the same as Clay’s Ark. But you can’t read it (unless you want to pay at least $60 for a second-hand copy) so it doesn’t matter whether I recommend it or not.